By the time of the American Civil War, Augusta had become one of the South’s few manufacturing centers. The Canal was a factor in Confederate Col. George W. Rains selecting Augusta as the location for the Confederate States Powder Works. The only buildings ever constructed by the government of the Confederate States of America, the 28 Powder Works structures reached along the Canal for two miles. Other war industries established themselves on or near the Canal, making Augusta a critical supplier of ammunition and war materiel.

Unlike some other Southern cities devastated by the Civil War and General Sherman’s march through Georgia and South Carolina, Augusta ended the war in “better condition than any other cities in this section of the South,” reported the Augusta Chronicle in December 1865. The population had doubled and hard currency was available to finance recovery. The Canal’s Chief Engineer William Phillips suggested enlarging the Canal to mitigate recurring flooding, a feat accomplished by 1875.

Boom years followed as massive factories including the Enterprise, King and Sibley textile mills, the Lombard Ironworks and many others opened or expanded. Farm families migrated to the city for factory jobs as “operatives.” Largely employing women and children, some as young as seven or eight, the factories led to the rise of several “mill villages” in their precincts. Workers who took part in labor strikes and stoppages in the late 19th Century sometimes found themselves put out of their modest, company-owned dwellings.

By the 1890s working conditions in the mills – 11½ hour days, work speed-ups and pay reductions – and living conditions in the mill villages created a climate ripe for labor unrest. National labor organizations sent organizers who initiated a number of unsuccessful strikes. According to historian John S. Ezell, “Textile unionism took its last big chance in Augusta in 1902 and lost.”

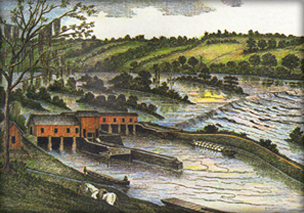

-

Canal Headgates 1875

-

Spinner girl at an Augusta Mill

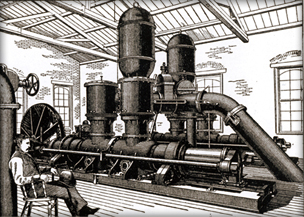

In the 1890s the city replaced its old water pumping station with the impressive structure at mid-canal that is still in use today. As the electric age began to dawn, the city turned to the Canal’s falling water power to drive the first electrical generation equipment. By 1892 the city boasted both electric streetcars and street lighting – the first Southern city to have these amenities.

Gradually Augusta’s factories converted from canal-driven hydro-mechanical power to electrical power. The city devised a number of schemes to build a hydro-electric plant on the Canal. None were carried through to completion.

Turbines in the 1898 Waterworks Building

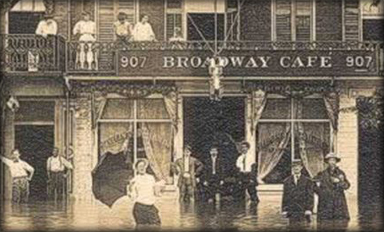

Periodic floods, which plagued the Canal and Augusta for decades, continued to cause damage during the early 20th Century. Following major floods in late 1920s and early 30s, the Federal Works Progress Administration deployed hundreds of workers to make repairs and improvements, including raising the banks, building a new spillway and straightening the Canal.

By the mid-20th Century, the Canal entered a period of neglect. Textile mills began to close and the center of Augusta’s industrial activity shifted south of the city. Although still the city’s drinking water source, the Canal was no longer the driving force for development it had been 100 years before. At one point in the 1960s, city officials considered draining the Canal and using the dry bed as the course for a superhighway.

Flickers of interest in reviving the Canal for recreational use began to appear by the mid-1970s. A state park was proposed and efforts made to have the canal and its 19th Century mills declared a National Historic Landmark. While the state park never materialized, growing public interest in the Canal’s historic and scenic potential led to several important developments. The Canal and mills were listed on the National Register of Historic Places and later declared National Historic Landmarks. In 1989 the Georgia State Legislature created the Augusta Canal Authority, the body that has jurisdiction over the Canal today. In 1993, the Authority issued a comprehensive Master Plan, outlining the Canal’s development potential. In 1996, the U.S. Congress designated the Augusta Canal a National Heritage Area.

In the 21st century the Augusta Canal is once again a source of pride and potential for its community. The mighty Enterprise Mill, revived after years of neglect as an office and residential complex, now houses the Augusta Canal National Heritage Discovery Center. Its exhibits and artifacts depict Canal construction and mill life and remind Augustans and visitors alike of the progress, problems and promise of the Augusta Canal.

Source: Edward J. Cashin, “The Brightest Arm of the Savannah: the Augusta Canal 1845-2000,” Augusta, Augusta Canal Authority 2002) Compiled by Rebecca Rogers, March 5, 2003, revised March 24, 2014

READ MORE ABOUT IT in the Historic Engineering Record (HAER)

Order your copy of the

award-winning history

of the Augusta Canal by

Dr. Ed Cashin

$27.95 hardbound

$18.95 softbound

plus tax & $3.00 s&h

1-888-659-8926

Visit the National Park Service "Discover Our Shared Heritage" Augusta Website